Two Years in the Life of a Pandemic: Listening To the Voices of Parents

In early April of 2020, our team launched the first RAPID national household survey to understand—and bear witness to—the experiences of families with young children in the US during the COVID-19 pandemic. As child development researchers, advocates, policymakers, and funders, we wanted to know more about how disruptions to everyday life, social isolation, uncertainty about the future, and numerous related stressors would affect child and family well-being. We also hoped that this information could inform policy and programs that support children’s well-being in the weeks, months, and years that lay ahead.

Through the survey, we sought to create a holistic picture of children in the context of their parents and communities. We asked about such topics as parent and child emotional distress, economic circumstances, and access to healthcare and child care. We knew that the survey needed to include families across racial and ethnic groups, at all income levels, and from all regions of the country. We also knew that the survey needed to be conducted on a regular basis to look at the dynamic effects of the pandemic as it unfolded over time; and we understood that we needed to turn the data around and disseminate it quickly to key stakeholders at federal, state, and local levels.

In the ensuing two years, the RAPID survey gathered information from 13,758 parents of young children through 94 surveys. In March of 2021 we added a survey of the early childhood provider workforce, and since that time have fielded 51 workforce surveys with data gathered from 2,599 child care providers. Our household and child care workforce surveys include participants in all 50 states, and respondents are diverse in terms of race, ethnicity, income, and family structure. We have built an extensive and growing quantitative dataset from these surveys and have also collected over 260,000 written responses to a set of open-ended questions included in each survey.

We deeply appreciate the families and child care providers who have partnered with us to share their experiences over the past two years; our team members who have collected, analyzed, and disseminated the data; and our partners in policy, advocacy, research, and philanthropy who have contributed their time, expertise, and other resources to this work.

This report contains a summary of key findings for the first two years of the RAPID surveys. The topics and trends we have been following (e.g., the prevalence of economic hardship, an inadequate supply of child care providers relative to demand, structural inequalities based on race and ethnicity—as well as the resiliency of families and providers) provide a living record of the pandemic. However, these issues didn’t begin in 2020 when the country locked down. These are longstanding issues and will continue to challenge young children and the adults in their lives well after the pandemic has faded into history.

Below are five key findings from the first two years of the RAPID survey.

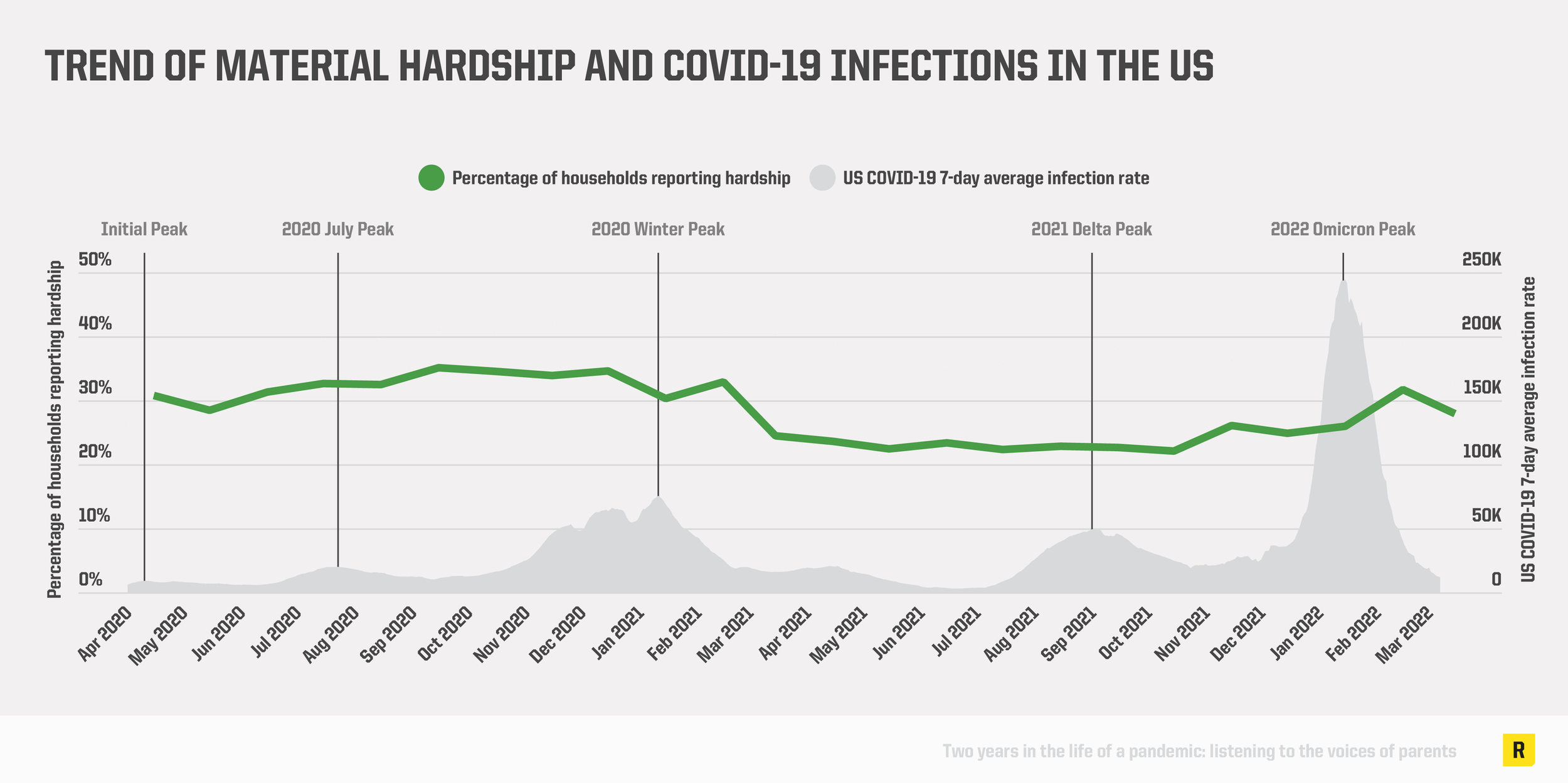

1. Rates of material hardship have been high throughout the pandemic, and are negatively affecting parent and child well-being.

We have measured rates of material hardship (defined as difficulty paying for basic needs, such as food, housing, utilities, child care, and healthcare) in all of our surveys dating back to April 2020. From the beginning of the pandemic through February 2021, the percent of families having difficulty paying for at least one of these basic needs was consistently above 30% (representing more than 4 million families). This figure decreased to approximately 25% from March 2021 to January 2022, but then increased in February 2022 to 32%, one of the most dramatic one-month increases in hardship that we have seen since we started collecting data. Parents reported the most difficulties paying for utilities, food, and housing.

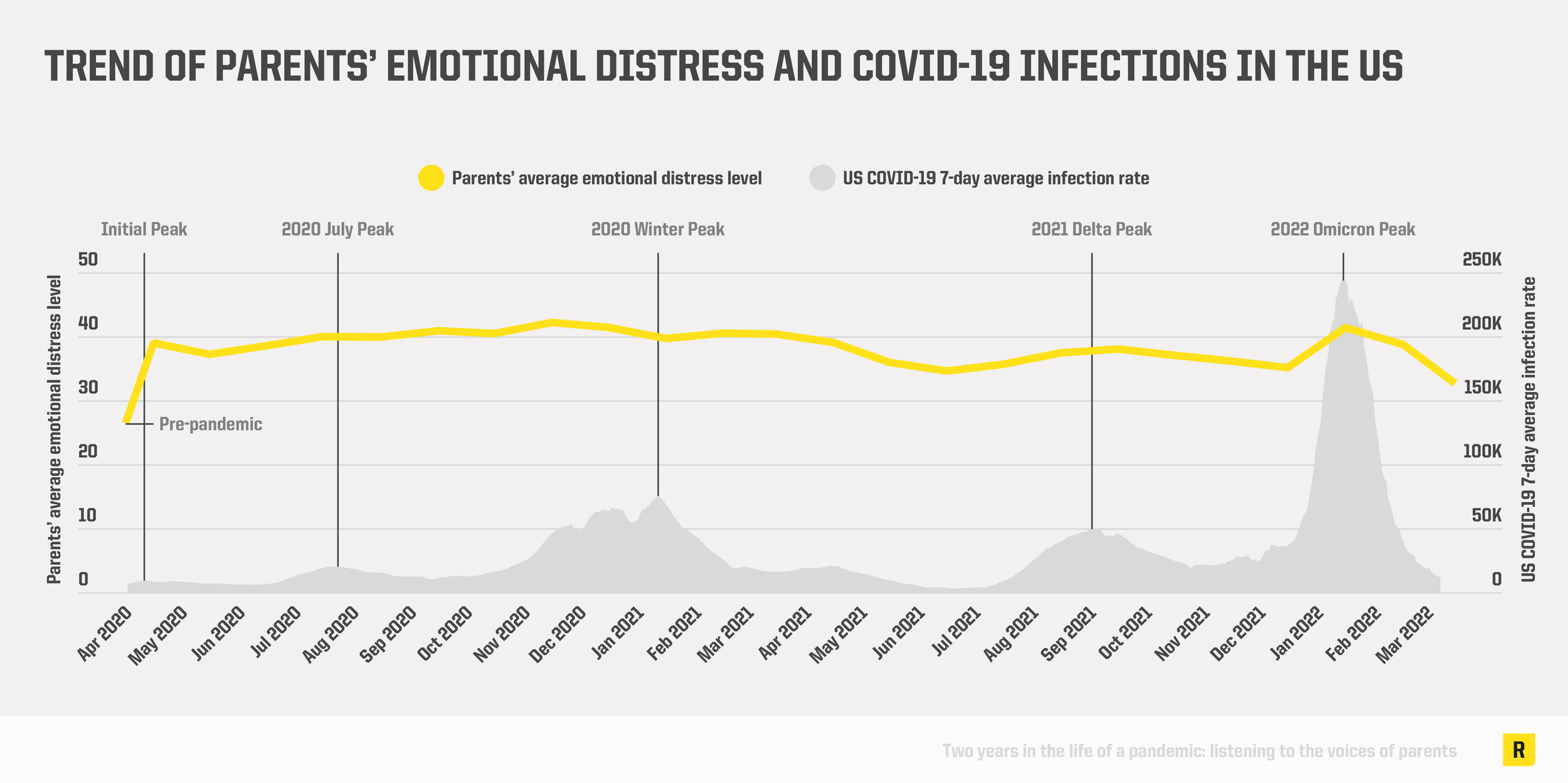

We have also examined parents’ emotional distress on a 1-100 scale as a composite of symptoms of depression, anxiety, stress, and loneliness. Throughout the pandemic, we found that parents of young children consistently experienced elevated levels of emotional distress compared to what they reported pre-pandemic.

Notably, although we cannot determine if there is a causal relationship, the levels of material hardship and parents’ emotional distress appeared to rise and fall in parallel with U.S. COVID-19 infection rates.

We also measured children’s emotional distress on a 1-100 scale as a composite of their internalizing (fearful/anxious) and externalizing (fussy/defiant) behavior reported by their parents. Levels of child emotional distress perceived by parents since the start of the pandemic have been significantly higher compared to their pre-pandemic levels and have been relatively stable over the last two years, with a slight decrease observed in recent months.

One of the most noteworthy findings has been a consistent chain reaction of hardship. In 2021, we reported that an increase in material hardship in one week was associated with an increase in parents’ emotional distress in the subsequent week, which, in turn, was linked to an increase in children’s behavioral problems in the weeks that followed. This chain reaction of hardship has remained in place throughout the two years of RAPID surveys.

|

[My biggest challenge is] that I need better health insurance for my son and I but can’t afford it. I also recently took a new job that paid more and had more opportunity, but still not enough to cover childcare, so I’ll be paying that with a credit card.” - Parent in Illinois

I live off paycheck by paycheck, so with the increased rate of EVERYTHING somedays I have to choose if I am eating or not so I can provide for my kids. - Parent in Minnesota |

In the summer of 2021 through the end of the year, the federal government provided an expanded Child Tax Credit (CTC) to families as one component of pandemic support and recovery. During the time that it was in place, 76% of households in our national survey reported receiving the payments. We found that monthly CTC payments buffered families from material hardship and financial difficulties. In our survey data, nearly 60% of parents indicated that they used the monthly payments for basic needs, and over half of parents said they used the payments for unpaid bills and other essentials (including child care costs). We also found that among those who did not receive CTC payments the proportion of families reporting material hardship steadily increased. In contrast, material hardship rates among households who did receive CTC payments did not increase during the time the CTC was in effect.

|

[The Child Tax Credit] has greatly improved my financial situation and provided a safety net of money every month to cover rent and expenses. - Parent in New York

I can’t even put into words what [the Child Tax Credit] means. It's literally the difference between paying a bill or buying groceries, kids clothes and basic necessities, and I appreciate that it will help me keep groceries in my house. - Parent in Kentucky |

2. The unpredictability of material hardship has additional negative effects on parent and child well-being.

In addition to elevated levels of material hardship and the effect that this had on children and families, we also saw that families with young children have experienced high levels of material hardship unpredictability—week-to-week and month-to-month changes in being able to pay for basic needs—since the beginning of the pandemic. Moreover, unpredictability of material hardship significantly and negatively affected parents’ and young children’s well-being. These effects were above and beyond the the negative effects of the level of hardship that a family experienced.

This highlights that, in order to support parent and child well-being, it is critical to not only provide adequate financial resources and assistance but also to promote stable financial conditions.

One potential way that material hardship unpredictability affects well-being is by disrupting family routines, such as regular bedtime, morning activities, and having family meals together. Interruptions in regular family routines, in turn, were associated with more emotional distress among both parents and their young children. This finding is aligned with numerous other studies that highlight the role that family routines have played in maintaining well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The good news is that we found parent-child quality time (as defined by parents themselves) lessened the weight of these challenges and served as a protective factor. Although disrupted family routines were linked to more emotional distress for both parents and children among families that reported less quality time spent together, disrupted family routines did not lead to elevated emotional distress among parents who spent more quality time with their children during the pandemic.

|

Money [is our biggest concern]. My husband was sick for three weeks and he's self employed, so no money for a month. I really want to go back to work but there's no daycare openings for three kids and the school closes too much for me to get a job. - Parent in Maine

Uncertainty about what comes ahead. No idea what our jobs will be, if we will have enough money, if we'll get childcare, where we'll live, what we'll be able to do, and on and on. - Parent in Montana We need to be able to keep our Medicaid healthcare. My husband got a $2 an hour raise which is potentially going to affect our health insurance. We CAN'T afford to pay for it on our own! We can barely get food for ourselves. - Parent in Pennsylvania |

3. Families with young children experience disruptions to child care, while child care providers face increased hunger, hardship and disruptions to employment.

Families with young children who are seeking child care are experiencing difficulties finding care and disruptions to the child care arrangements. In the past year, with the launch of our RAPID provider survey, it has become clear that child care providers have been facing significant challenges also, in terms of their financial circumstances, work conditions, and disruptions to employment and work schedule due to COVID-19. These challenges are two sides of same coin, and are having negative effects on the well-being of child care providers, parents, and young children.

For families with young children, inability to find care and disruptions to their current child care arrangements are associated with increased emotional distress for both parents and their children. The percent of parents having difficulty finding child care peaked between January and February 2022 (43%) with the emergence of the Omicron variant. Additionally, parents who experienced difficulty finding care and/or disruptions in care indicated higher levels of emotional distress compared to those who did not experience child care difficulties.

For child care providers, rates of material hardship and hunger have remained high, with approximately one in three child care providers consistently reporting experiences of material hardship or hunger in the past year of the pandemic. Experiences of material hardship and food insecurity were particularly high among child care center teachers and family, friend and neighbor (FFN) providers. Moreover, one in four child care providers reported having at least one other job, and over 40% indicated that providing child care accounted for less than half of their income.

Child care providers have also reported challenges with unstable work schedules, staffing shortages, as well as frequent cancelations and closures. For example, in November 2021 we reported that nearly 60% of center- or home-based providers were experiencing staff shortages due to difficulties recruiting and retaining qualified staff. This was a significant increase from before the pandemic (36%). The reasons behind this trend include low wages, burn out, no or unsatisfactory benefits, health/safety concerns, and lack of child care for providers’ own children. Staffing shortages, along with the rising COVID-19 infection rates with the emergence of virus variants also led to high rates of child care closure and cancelation. Our data from both household and provider surveys show that the rate of closure/cancelation peaked at the beginning of 2022 with the emergence of the Omicron variant.

These financial and workplace challenges have affected child care providers’ well-being. Emotional distress levels among providers increased when they experienced 1) more material hardship, 2) more hunger, 3) more uncertainty/instability in their work schedule, and 4) more cancelation/closure. We also found a concerning trend that many (38%) providers were considering leaving the workforce or closing their child care programs. This would cause even more staffing shortages and recruitment/retention difficulties in the child care workforce, making it even more difficult for parents to find child care for their young children.

|

[My biggest challenge is] finances and the amount of stress I’m under at work. The schedule constantly changes and we're understaffed. I work 10 hour days with no breaks. - Center teacher in Colorado

[My biggest challenge is] getting and paying for child care for my own school age child. Managing the extreme stress of keeping the child care center afloat and taking care of the teacher's stress/emotional load while balancing with my own family's needs. The work is 80 hours a week. I'm a single mom. This is too much, with my daughter unable to go to school 5 days/week. - Center director in Virginia No paid sick leave, no paid time off, long hours, getting burnt-out, little pay. - Home-based provider in Minnesota |

Many of these difficulties experienced by the child care workforce predate the pandemic and will likely continue with the ongoing possibility of new COVID-19 variants. Prioritizing stability for parents and children and supports for child care providers, including financial assistance and increased compensation, are essential to guaranteeing a functional child care system that adequately protects and uplifts its workforce and that allows parents to return to work and support their young children.

|

[Not having] stable, reliable daycare [is our biggest challenge]. Not being able to provide routine for my kids. Not being able to focus on paid work during the day and not juggling work and childcare at home. - Parent in North Carolina

My daughter is enrolled in daycare but the month of January has been one COVID closure after another. Today is January 20 and she has had a grand total of 4 days of daycare this month. - Parent in California |

4. Long-standing structural inequalities have persisted and grown more acute during the pandemic.

Throughout the two years of RAPID surveys, we have observed consistent inequalities based on families’ income level, race/ethnicity, and family composition. These inequalities are long-standing and woven deeply into the structures that support children and families in this country. They existed prior to the pandemic and have widened since.

Not surprisingly, material hardship and hardship unpredictability were higher among lower-income households (i.e., below 200% federal poverty level; FPL) as compared with middle and higher-income households. When comparing families of different racial/ethnic groups, we observed that Black and Latinx families have not only experienced more material hardship than White families, but also had to cope with more hardship unpredictability. Similarly, single-parent households and families of children with disabilities reported higher levels of material hardship and hardship unpredictability compared to dual-parent households or families of children without disabilities.

There are similar disparities in emotional distress levels across these subgroups (although, notably, not in terms of race/ethnicity). In lower-income families, single-parent households, and families of children with disabilities, parents reported significantly higher levels of emotional distress than in higher-income, dual-parent households, or families of children without disabilities. These findings suggested that certain socio-demographically marginalized groups have been bearing a heavier load throughout the pandemic as a result of structural and systemic inequalities.

|

[My biggest concern is] medical coverage. I'm disabled but I've been kicked off disability for a while now. But I still need my medications. I got kicked off my parents insurance in March after turning 26. - Parent in Michigan

My biggest concern is to make sure that my child is having proper care and her future schooling will be good. We always remain tensed that she might face discrimination due to her race/ethnicity specially after the pandemic. - Parent in Utah |

5. Amid these difficulties, parents and child care providers also focus on what has helped during the pandemic.

In spite of all the challenges discussed above, families with young children and child care providers have also shared what has been helping them cope with stress. Analysis of responses to the open-ended question: “What is helping you and your family the most right now?” show that both parents and providers identified external sources of support such as extended family, friends, and co-workers as helping the most. Parents of young children also indicated that flexible working arrangements, employment security, schools reopening, and maintaining daily routines were factors that further contributed to their resilience during this unprecedented time. Child care providers indicated that funding and grants from the government or social organizations have been major supporting factors. The top 10 most prevalent topics from parents and providers are presented below.

Top 10 factors that help families with young children

|

Top 10 factors that help child care providers

|

|

Medicaid has made changing careers possible for me. Childcare scholarships have made an incredible preschool possible for our child. - Parent in New Jersey

Having paid parental leave at both our jobs [has helped us]. We would be much more concerned about the pandemic’s effects on our newborn if we had to enroll him in childcare now versus when our leave is up. - Parent in Maryland A restoration grant saved my business! - Home-based provider in Illinois My friendship with my co-teacher is the only thing keeping me going in this field at the moment. - Center teacher in Colorado [What has helped me most is] I am a part of a national ECE directors group that meets weekly, and I have a small cohort of local directors with whom I can vent and share ideas. - Center director in Louisiana |

Implications

Young children, parents and child care providers need ongoing social and economic support, not only to cope with the stresses brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, but to be able to experience the stability that can help all children and adults thrive. As young children return to child care and preschool, special attention should be paid to the importance of social connections and family support. It is critical that the issues facing the child care system are addressed, so that all families can access child care when they need it and providers can experience economic stability, support their families, and continue to provide the attentive care that children and families rely on. As policies emerge to address these challenges, we should collectively turn to the voices of parents and child care providers to inform the path forward.

Looking ahead

We are continuing to field the national RAPID surveys. Many of the challenges and areas of resilience that we have observed during the two years of the survey pre-date the pandemic and will continue into the future. The RAPID surveys allow us to listen to families at frequent intervals and get a holistic view of the factors shaping the circumstances in which young children are developing and the impacts of those circumstances on the important adults in their lives. Through RAPID we have seen how children’s and families’ lives have changed in response to changes in the world around them. We will continue to use this tool to listen to and learn from parents and families as we move into the next phase of the pandemic and beyond. RAPID is an essential tool and resource for all of those working to better support children and families and the child care providers they rely on.

In addition to the national work, RAPID is expanding in several ways:

Launching local surveys in communities, cities, and counties to provide actionable population-level data that can be used to support families, young children and the local programs, organizations and government agencies that work on their behalf.

Launching state surveys to provide policy makers, systems leaders, and advocates with key information to facilitate allocation of funds to support children, parents, and the early childhood workforce.

Partnering with measurement experts to add new content to RAPID in areas associated with child psychosocial development, family environment, and health.

RAPID is only one component of the collective impact work needed to achieve the full potential that the US early childhood ecosystem aspires to—of creating equal opportunity for all children, regardless of geography, economic circumstances, race or ethnicity.

About RAPID

RAPID surveys are designed to gather essential information continuously regarding the needs, health-promoting behaviors, and well-being of young children and the important adults in their lives. RAPID collects data monthly from 1,000 caregivers and 1,000 child care providers in all 50 states. The samples are large and the surveys are national in scope, however, the data are not technically representative of households with young children in the US. Additionally, the surveys are available in English and Spanish and can be taken on any device with an internet connection, but our samples are limited to those who have access to these resources and who speak English or Spanish. RAPID employs a unique data collection strategy and, as such, the data are a combination of cross-sectional and longitudinal. For more information about RAPID study design and methods, visit this page.

The following individuals contributed to this report: Philip Fisher, Joan Lombardi, Nat Kendall-Taylor, Sihong Liu, and Cristi Carman. We are also grateful to the RAPID National Advisory Council for input on survey content, data analysis and interpretation, and dissemination of results. We thank all of the families and early childhood care and education providers for their participation in the past two years of surveys.